This Month’s Featured Article

The 29th Connecticut Infantry

While the Civil War has been the subject of nearly 100,000 books, there are, amazingly, still important stories to be told. One such story is that of the 29th Connecticut Infantry, an African American unit nearly forgotten by history. It is the subject of but one book, and the two monuments to the regiment were constructed within the last twelve years. Yet the story of the 29th Connecticut is an important one; collectively their service had implications for the nation’s future and individually its members made tremendous sacrifices. The regiment faced an evening of terror in a forgotten battle outside Richmond, and experienced a supreme moment of triumph at the war’s conclusion.

While the Civil War has been the subject of nearly 100,000 books, there are, amazingly, still important stories to be told. One such story is that of the 29th Connecticut Infantry, an African American unit nearly forgotten by history. It is the subject of but one book, and the two monuments to the regiment were constructed within the last twelve years. Yet the story of the 29th Connecticut is an important one; collectively their service had implications for the nation’s future and individually its members made tremendous sacrifices. The regiment faced an evening of terror in a forgotten battle outside Richmond, and experienced a supreme moment of triumph at the war’s conclusion.

An African American regiment

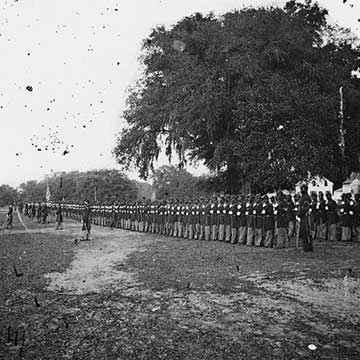

As the Civil War dragged on, President Abraham Lincoln issued repeated calls for more troops. Spurred on by the fear of a draft if enlistment quotas weren’t met, in November 1863 the Connecticut legislature authorized the raising of an African American regiment, which became the 29th Connecticut. Within a month, men were pouring into the newly-established training camp in New Haven. While one estimate states that nearly 80% of Connecticut’s African American men of military age served – a figure double the rate of enlistment in the North as a whole – enlistment in the 29th was boosted by recruits who crossed the border from New York State, which did not yet have a regiment of its own in which African American men could serve. Research by Housatonic Valley Regional High School students has found no fewer than twenty-five men enlisted from the six towns that comprise the Region One school district. Two of these men crossed the border from New York to enlist.

In New Haven the men received military training and equipment equal to white soldiers, with one exception. As an African American unit, the 29th Connecticut did not receive its rifles until it had reached the South. While in camp, the regiment was addressed by Frederick Douglass, who succinctly and powerful told the men what was at stake: “You are pioneers of the liberty of your race. With the United States cap on your head, the United States eagle on your belt, the United States musket on your shoulder, not all the powers of darkness can prevent you from becoming American citizens. And not for yourselves alone are you marshaled – you are pioneers – on you depends the destiny of four millions of the colored race in this country. If you rise and flourish, we shall rise and flourish. If you win freedom and citizenship, we shall share your freedom and citizenship.”

Inspired by Douglass, outfitted with a flag by New Haven’s African American community, and cheered by thousands as they paraded to that city’s wharves, the men of the 29th sailed off to war on March 19, 1864.

To the battlefields

After five quiet months of picket duty and manual labor, the 29th Connecticut was sent to the battlefields outside of the Confederate capital of Richmond. In late September the 29th Connecticut was involved in the seizure of Fort Harrison, a vital part of the Confederate defenses. Here the 29th suffered its first significant casualties of the war, with one man killed and seventeen – including Charles Carter of Litchfield – wounded. Despite ferocious Confederate counterattacks, the fort remained in Union hands.

While Fort Harrison is today preserved and interpreted by the National Park Service, the bloodiest day for the 29th Connecticut took place on a battlefield essentially lost to history. Only the most detailed microhistories of the Fall 1864 battles around Richmond mention the Battle of Kell House, but what happened there on October 27, 1864, deeply impacted the men of the 29th Connecticut, altering many lives forever.

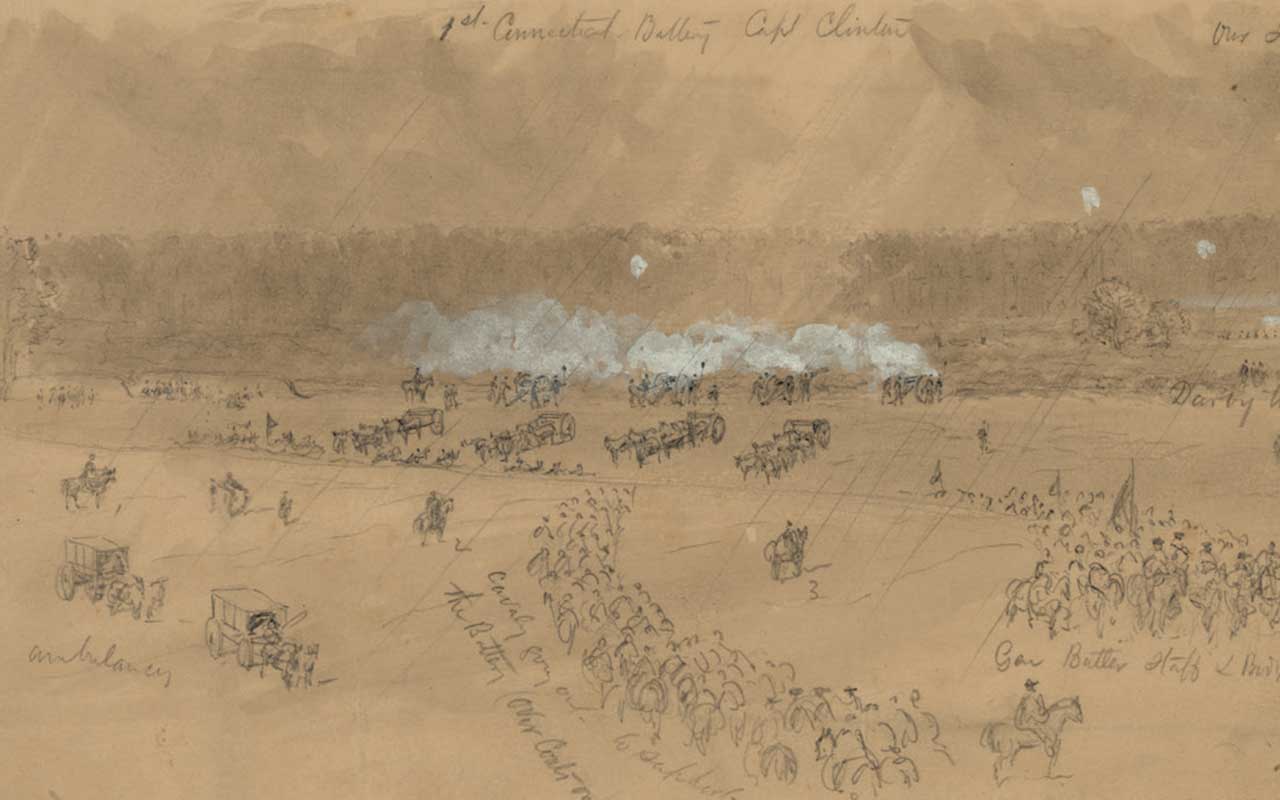

By October 1864, the fighting outside Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia, was entering its fourth month. Union commander General Ulysses S. Grant ordered a diversion against the Darbytown Road, a major avenue for supplying the Confederate army. Grant hoped this movement would occupy the attention of the Confederates, so that the major Union effort could be made against Petersburg, the communication and transportation hub for Richmond. To carry out this plan, the 29th Connecticut assembled at the Kell House, in what is now Henrico, Virginia, on October 27. Soon, they were advancing toward the Confederate entrenchments.

According to regimental commander Captain Frederick E. Camp, the 29th “skirmished through a thick wood for some distance, driving in a strong line of the enemy’s pickets, and advanced to a position on the edge of the woods near the enemy’s works.”

The Confederates opened fire. Lieutenant Henry Brown, remembered, “Bullets came fast. We were in the edge of the woods. ‘Halt! Lie down!’ was passed along the line. The men, much to my surprise, I admit, obeyed as ready as in drill.” Having taken the position, Brown recalled, the regiment was to “hold it at all hazards until we had orders to fall back.” The enemy pickets made easy targets as they ran for the cover of the entrenchments. “We took delight in hitting them,” remembered Captain Edward Bacon. The fighting was so intense that men of the 29th forgot to remove their ramrods from their rifles, and these hurtled through the air like missiles. The Confederates were driven back to their main line of defense, and the 29th took up a position only 200 yards from the rebels. Here, Captain Camp remembered, the regiment remained for hours, “exposed to a hot fire … all day and night.” The artillery fire was especially severe, and Brown recalled, “Soon grape and canister came in among us.”

At 8pm, the 29th was ordered to pull back, but it was too dark to successfully carry out that maneuver. They were forced to remain on the skirmish line overnight. When finally relieved the following morning, some men of the 29th Connecticut had fired as many as 225 rounds. In the army’s official report of the engagement, the 29th was commended for having “behaved very well.” Meanwhile, the flanking operation conducted by the 18th Corps ended in failure, with Union troops unable to break through. Confederate casualties along the Darbytown Road numbered about 100 men, while the Union lost 1600, including 11 men killed and 69 wounded from the 29th, its greatest loss of any battle in the war. Among these were two dead and five wounded from Connecticut’s northwest corner.

The wounded

Among the 29th’s wounded was William Glasgow, 22, of The Hills, an African American enclave near White Plains, NY. Since New York did not sponsor black regiments, Glasgow and 15 others crossed into Connecticut to enlist. At the recruiting office in Bridgeport, he gave his residence as Salisbury, CT. Glasgow had been with the 29th for nearly eight months before Kell House. He was struck by a bullet in his left thigh and was taken to a field hospital, where his “left leg lower third” was amputated. He spent the rest of the war in a hospital in Fort Monroe, Virginia, until being discharged on August 7, 1865.

Other members of the 29th came from farther afield. Joseph Parks was born in Valparaiso, Chile, and worked as a sailor. When the ship he worked on docked in New York City in 1863, Parks accepted money as a substitute for Lemuel Deming of North Canaan. A loophole in the Enrollment Act granted an exemption from the draft for anyone who hired a substitute. This practice led to the perception of many that the war was a “rich man’s war” but a “poor man’s fight.” A number of prominent Americans would use this method to avoid service, including John D. Rockefeller and the father of Theodore Roosevelt.

Parks was assigned to the 29th, and was with the regiment at Kell House. Early in the action he was shot in the left side of his face, causing a severe jaw fracture. Parks was conscious throughout the surgery he underwent at Bermuda Hundred, Virginia. However, he died from complications of this surgery on November 6, 1864. Lemuel Deming, who paid Parks to take his place, lived until 1899, dying at the age of 76.

After the battle

Following the Battle of Kell House, the 29th returned to the trenches outside Richmond. The next five months saw little action. Then, on April 3, massive explosions indicated the Confederates were evacuating Richmond. Marching rapidly, the 29th Connecticut became the first Union infantry regiment to enter the Confederate capital. There, on April 4, the men of the 29th came face-to-face with Abraham Lincoln, who had rushed to Richmond in the hopes of seeing firsthand the war’s final scenes. Lincoln was swarmed by African American residents of the city. Addressing the crowd, Lincoln said, “You are as free as I am, having the same rights of liberty, life and the pursuit of happiness.” When Lincoln commented on the number of men who had lost their lives in the cause of ending slavery, Alexander Newton of the 29th remembered crying, but noted, “They were tears of gladness and sorrow, of regret and delight; but the tears of my own people were the tears of the greatest joy.” Five days later, Robert E. Lee surrendered to

Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House.

For many black veterans and their families, the end of the war began another battle. Men who were wounded, wracked by illness, or injured in the war could not work when they returned home. While the government offered pensions, these were often difficult for the men of the 29th to procure. For example John Watson of Cornwall had fought with the 29th from March 1864 until the end of the war. When he died in 1874, his wife Harriet applied to collect his pension. She was denied on the grounds that she could not prove her marriage to John was a legal one. As was common among African American couples, they had never obtained a legally issued marriage certificate. Eventually, she would have to produce ten witnesses to testify on her behalf before finally being allowed to collect John’s pension in 1891.

For the men of the 29th Connecticut, the Civil War was unquestionably a struggle for freedom and the destruction of slavery. And while theirs is a story of triumph, it is also a story of sacrifice. For many of the men, the struggle and sacrifice continued well after the guns went silent.

By Shane Stampfle & Peter Vermilyea

Shane Stampfle is a member of the Class of 2020 at Housatonic Valley Regional High School, where Peter Vermilyea teaches history. For more information on the 29th Connecticut, see ProjeCT29, a website developed by Housatonic students about the regiment, www.project29.org.